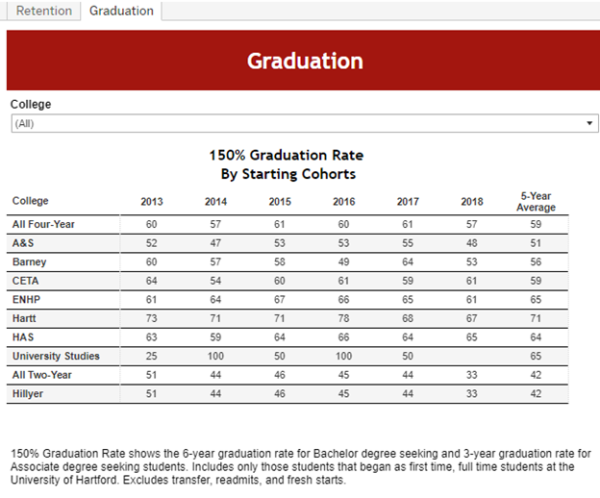

Two of the greatest challenges UHart has faced over the years are student retention and graduation rates. From 2014 to 2018, around 59% of UHart students graduated from four-year programs. That means the starting cohort for each graduation year only saw about 3-in-5 students graduate on time. Hillyer’s two-year program posted the lowest 5-year average graduation rate across this period, with a 42% graduation rate. On the other hand, the Hartt school posted the highest numbers during this duration, with a 71% graduation rate.

Over the past five years, the university possesses an average First to Second Year Retention Rate of 76.3%. During this period, the retention rate saw an initial decline from 78.4% in 2019, to 74.4% in 2020, and again to 71.9% in 2021. This trend reversed in 2022, when the retention rate increased to 76.6%, and continued into 2023, when retention reached 80.3%. The schools with the highest average retention rates over this period were: The Hartt School (86.4%), The Hartford Art School (83.7%) and CETA (82.0%). The schools with the lowest average retention rates were: Hillyer (58.3%), Arts and Sciences (73.5%), Barney (75.8%) and ENHP (78.0%).

The most obvious explanation for the decline and rise of retention rates over the past five years is COVID-19’s devastating impact on education and public life. In spite of this, the positive trend from 2022 and 2023 seems to have continued into 2024. According to R.J. McGivney and James Shattuck (co-chairs of the Retention and Student Success Committee):

“This fall, the University saw its best full-time bachelor’s degree-seeking first- to second-year retention rate in its history at 83%. The retention rates for Pell-eligible and first-generation students also increased from last year, up 5% for Pell-eligible students to 77% and up 6% for first-generation students to 78%. The retention rate for BIPOC students was 78%, up 5% from last year. In fall 2018, our retention rate was 75%, so we have clearly made great strides.”

These numbers show a positive trend in retention rates that should not be overlooked. However, statistics do not always tell the entire story. To paraphrase a professor who wished to remain anonymous (we’ll refer to him as Professor Anonymous from now on), an increase in retention does not necessarily mean improvements in student effort and achievement. In other words, the challenges facing educational quality in the current era (AI, lack of motivation, diminished reading skills, and focus on career prep) are still present.

In many ways, these challenges were exacerbated by COVID-19. Now, it is time for higher education to handle the side effects. In the words of Professor Amanda Walling, “the pandemic created long-term disruptions involving academic preparation for college as well as aggravating social, emotional, and mental health challenges for students. So, I think that on average, students arriving now are less prepared for college-level work than they were 10 years ago.” The diminishing quality of student work was an issue before the pandemic, but the mental effects of social isolation and online school are still felt today, even as the university’s retention numbers rebound.

“At the public education level, I think parents/families continue to be involved in their child’s education but in some cases, have unintentionally created a culture where students are excused from meeting rigorous standards, rather than being pushed to achieve them.” (Professor Patrick Allen, on student effort and academic performance)

Professor Allen’s thoughts on student performance demonstrate that a cultural emphasis on achievement over learning has caused many learners to lose pride in their education. Professor Anonymous also pointed out that students have less motivation to succeed if they do not see career applications in what they are learning. These thoughts are related in a very significant way, because if students have no pride in their learning and they only see relevance in terms of career prep, the scope for creativity and motivation in the classroom is considerably diminished.

So, where does the university go from here? On the future, Mr. McGivney and Mr. Shattuck stated the following:

“To improve our 2nd to 3rd year retention rate, which will then help improve our graduation rates, we are exploring initiatives such as:

- Professional advisors/coaches for 2nd year students who struggled in their 1st year

- Working to decrease the gap of unmet need for upper-class students

- Working to increase 2nd year student participation in clubs and organizations so students are more connected to UHart

“President Ward has set goals of 90% first- to second-year retention, 80% graduation rate, and 90% placement rate, and we are confident these initiatives will help us meet these goals.”

President Ward’s new retention goals are encouraging, and it is good to see that he is focusing on these issues so soon after becoming UHart’s president. Hopefully his initiatives are also able to improve student motivation and academic excellence. Retention’s primary focus is getting students to physically remain at the university, but getting them to mentally focus is another matter altogether. If both of these issues can be solved in the coming years, UHart will send its graduates out into the world more prepared to excel and contribute to society than ever before.